Every weekday, around 3 p.m., schools across the United States release their students to homes where they are asked how their days were; without fail, the answer is only “good.” If all an education system can produce are students who think the last 12 years were just “good,” something needs to change.

Kelly O’Rourke, the principal of Camas High School (CHS), believes it is a school’s responsibility to provide opportunities for graduates to do well in society.

“It is making sure that academically, you’re providing all students on campus with something that’s going to help them be successful in whatever their choice is after school,” O’Rourke said.

Yet, most classes promote skills that will be useless upon graduation: memorization of facts, doing well on tests and finding the one “correct” answer. Some situations may call for these skills, but in the modern workforce, the skillsets provided to students do not come in handy enough to justify a system spending 180 days a year teaching them.

Teachers, who arguably have the most considerable responsibility, do their best to form creative ways to make the decades-old curriculum relevant to their students.

“One teacher that does [communicate the importance of the current curriculum in the real world] perfectly is Ms. Boring. I’ve always hated math, and when we were learning logarithms, she said, ‘If you’re ever gonna do taxes, you’re gonna do a logarithm.’ Then she would write out financial problems and we would do them,” CHS senior Will Wiese said.

Yet despite these efforts, by the end of the year, students forget enough of the material that teachers spend the rest of their time in class reviewing it.

I am an ex-military kid (“military brat,” as the slang goes) who has lived in eight different cities and attended eight other schools. I have gone to schools on military bases, been homeschooled and have attended schools with student populations ranging from the thousands to only a few hundred.

Each new place was a new opportunity, not for learning English or math, but to learn from experience; for example, how to speak well, confidently and appear competent. For many kids, that is what school is to them: a way to gain experience operating in a mini-society.

“[School] gives you experience with teachers you might not like, people you may not like, and it shows you how to adjust and act accordingly,” CHS junior Rowan Vance said.

However, it is not the system that teaches students to adapt but the students who teach themselves. Through bells and a strict schedule, students are supposedly “taught” punctuality and the importance of adhering to a standardized routine. However, it depends on the student; despite the number of schools and bells I have been subject to, I procrastinate chronically and am constantly late.

On the other hand, schools do not teach their students how to fit in or speak to figures of authority (both essential and necessary skills); kids learn themselves through observation and trial and error. The system is simply the catalyst for self-growth – to a certain extent.

As it has for over a hundred years, the American public school system still operates under the classic belief that hard work will bring success; it is a belief that no longer reflects today’s world.

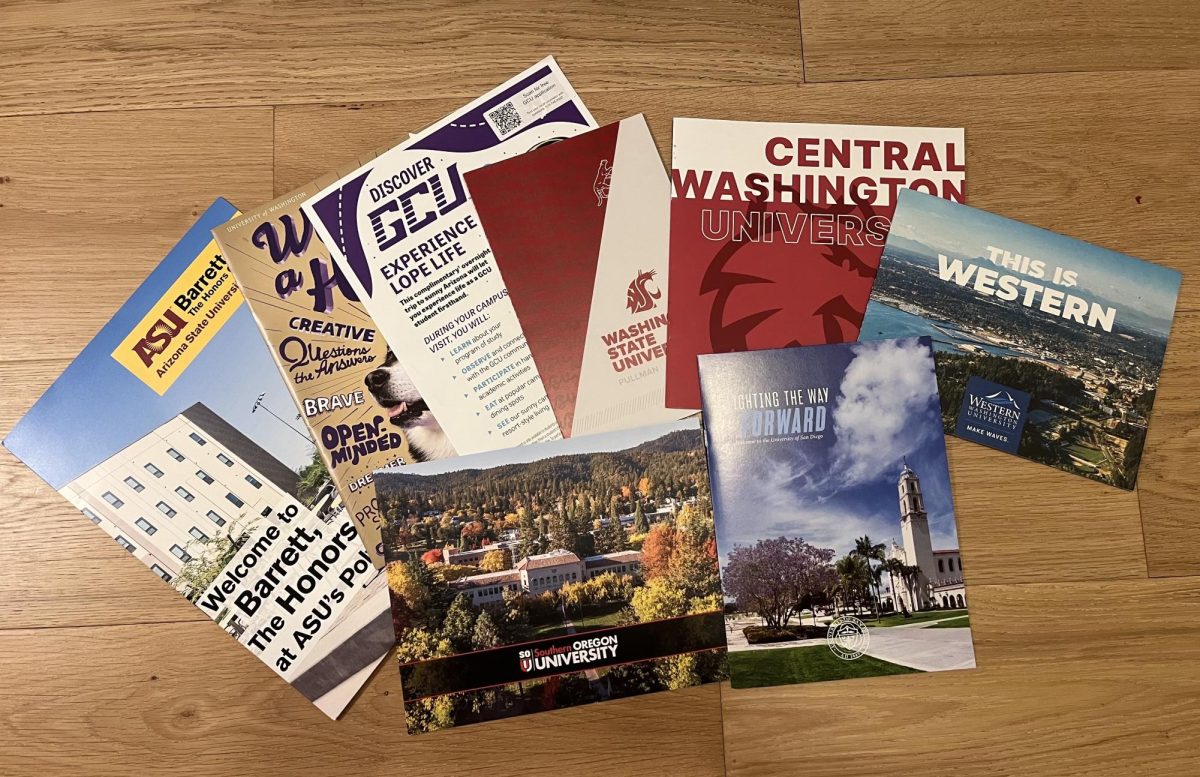

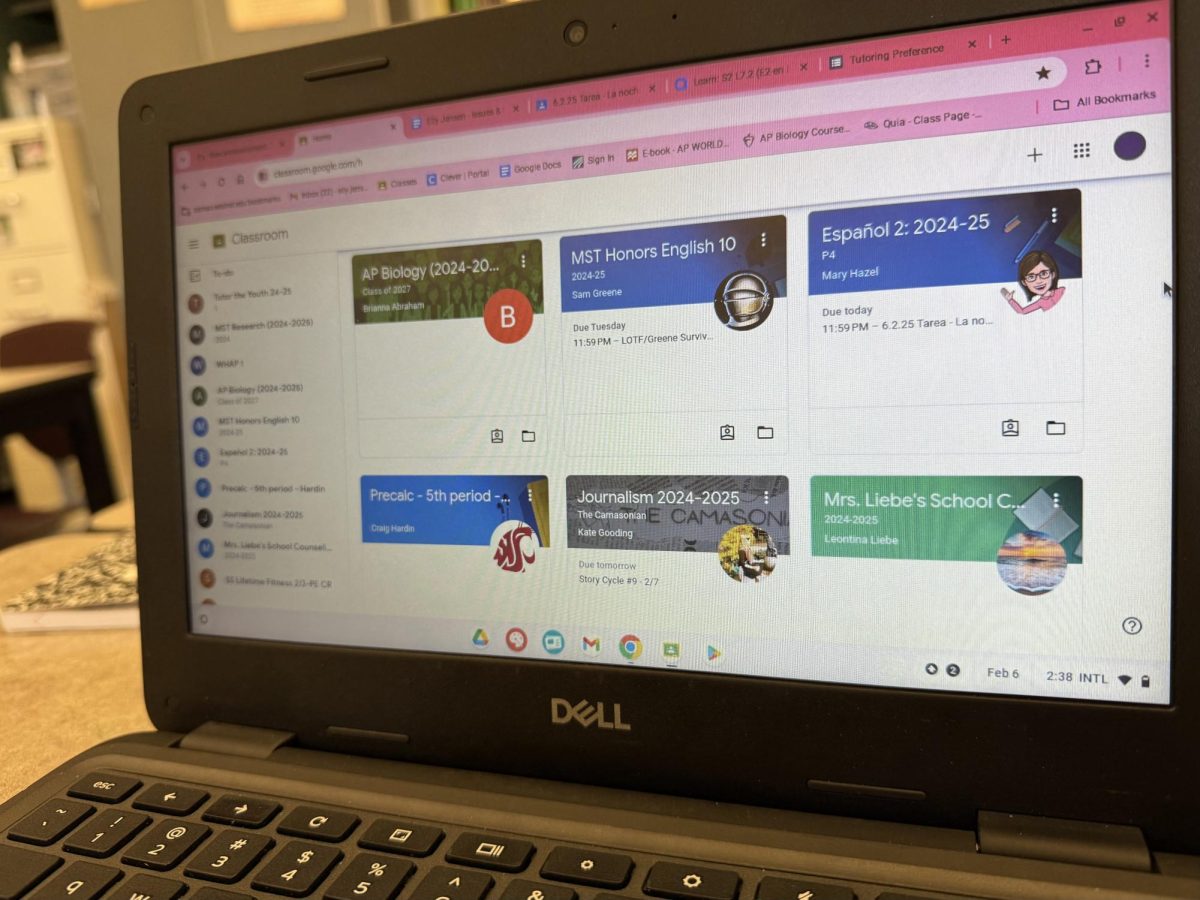

Students work until they are stressed and burnt out, hoping to get into a “good” university. I discourage myself from even attempting to start new things because there is not enough time to put in the hard work “necessary” for the attempt to be worth it. Instead, I stick to things I dislike, all for the sake of the “perfect” transcript.

There is not enough time, though the system, especially in high school, strives to provide students with opportunities to “find themselves.”

Throughout a student’s education career, the best opportunities come toward the end: the best art classes, sports options and the coolest classes. Unfortunately, there is only so much time to explore: four years, to be exact.

How can students be expected to already know themselves in a time of such change and exponential growth?

I have always excelled in the humanities. I do well in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), but I know I do best in history and English. As such, I have always gravitated toward those classes. Only recently, with the more advanced, technically focused classes CHS provides, have I realized how much I enjoy math and science.

However, it is too late. Most STEM careers require a graduate degree, and with my high school transcript proving my interest in STEM lackluster, it will be much more challenging to convince a university with a strong STEM program to accept me. That is, in part, why project-based learning (PBL) schools have started to become more popular.

Students of PBL schools like Odyssey Middle School (OMS) and Discovery High School (DHS) find that in addition to a more free-form daily schedule, the projects that this genre of learning encourages support experimentation. Students are not only able to “teach themselves” but also discover what they wish to learn.

“I like [PBL] because the projects have a longer time span, so you don’t have to focus on something and immediately focus on something else once it’s over. It ends up being bigger, and you can really see the fruits of your effort,” OMS graduate and current DHS freshman Kimberly Sun said.

However, most students prefer the traditional learning route CHS offers. Hence, there is a larger student body at CHS compared to DHS. This is not necessarily because more people learn better with the conventional system but somewhat due, at least partly, to the stigma surrounding PBL schools.

“I feel like PBL is a good opportunity for students, but I think it hasn’t been executed well and there’s low attendance. In the future, I think there’s stuff that the school district could do to move forward, like improve attendance and how other students see these schools,” CHS senior Ethan Nygaard said.

So, though the system’s goal for its students is well-intentioned, at CHS, at least, I have not seen the result reflect that in myself or my peers.

Albert Einstein once said, “the measure of intelligence is the ability to change.” If a school claims to guide its students to reach their intellectual potential, it must first change.