Kwanzaa – The Last Fruits of the Holiday Season

December 19, 2021

The American holiday season of marketing, for decades, encapsulated prominent religious holidays like Christmas and Hanukkah. However, Kwanzaa, which is often considered the third main holiday in this grouping, has faded in prevalence over time.

Kwanzaa was created by Ron Karenga, a pan-African activist in 1966 as a Black “alternative” to Christmas, though not necessarily a substitution.

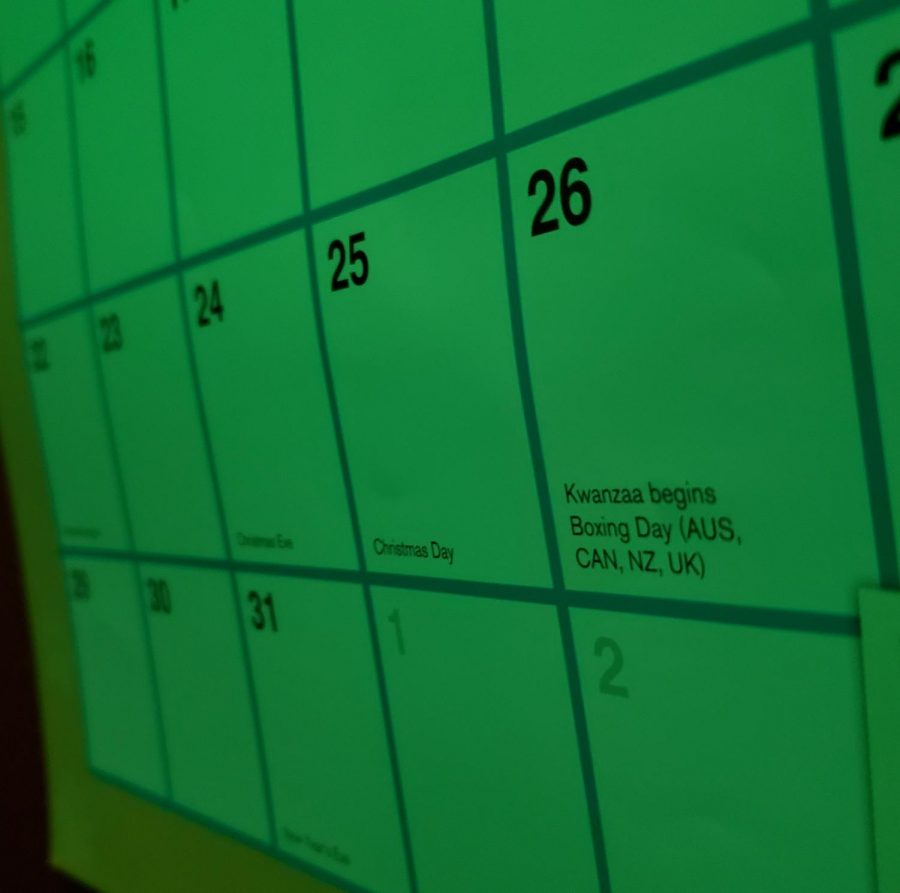

Kwanzaa occurs every year from December 26 to New Year’s day, the name of the holiday originating from the Swahili phrase of “matunda ya kwanza” which translates to “first fruits.” The holiday occurs around the general time of various African harvest seasons.

Karenga acknowledged that Black Americans do not generally base their lives around agriculture, yet Kwanzaa is used as an end-of-year celebration to symbolically enjoy each celebrant’s “fruits” of labor.

Kwanzaa contains elements of several mainstream American holidays, not only just Christmas and the New Year. The weeklong festivities celebrate a new principle and light a new candle on the kinara (similar to Hanukkah and its menorah), every day.

Despite an estimated 6 million people that still celebrate Kwanzaa, concentrations are sparse and centered primarily around major cities like New York, Chicago, and the Los Angeles area from which the holiday originated.

The Portland area is not one of those hubs, nor is the South, where Brian Witherspoon, a counselor at Camas and head of the school’s Black Student Union, is from.

“I’ve never really celebrated it. I don’t know that much about it.” Witherspoon said, which he speculated was on account of the prominent Baptist concentration in the South.

“[Kwanzaa] is a celebration that people in L.A. celebrated a lot.” sophomore John Staddon said, recollecting the exposure he had to the holiday from when he lived in L.A.

Bakersfield, California is only a two-hour drive from the holiday’s heartland of L.A., and it is also where sophomore Sophia Wade once celebrated the holiday when she was only five years of age.

“I don’t remember much, but we lit candles, danced to music, ate food, and listened to lots of stories,” Wade said.

The holiday also resonates to some as similar to American Thanksgiving, as the Karamu feast that occurs on the penultimate sixth day, serves as somewhat of a climax to the week that is so heavily based around food, whether it be through the feast or the harvest.

“It’s so cool how it combines patterns and philosophies from a ton of other celebrations,” Wade said.

With all of these similarities to other known American holidays, one can only ponder why very few schools educate about a holiday that is supposedly important enough to be mentioned but apparently not important enough to be explained.

“Kwanzaa is under-appreciated. I think it goes under the radar due to a lack of teaching about it.” Staddon said.

Each of Kwanzaa’s daily principles:

- Unity (Umoja)

- Self-determination (Kujichagulia)

- Collective work and responsibility (Ujima)

- Cooperative economics (Ujumaa)

- Purpose (Nia)

- Creativity (Kuuma)

- Faith (Imani)

All can be applied to anyone’s break. This holiday season can be spent celebrating both inner and collaborative peace, regardless of what you celebrate. So many elements from other traditions comprise Kwanzaa, and likewise, so many elements from Kwanzaa can be used to enhance anyone’s traditions.